The Future in Electric Hearts

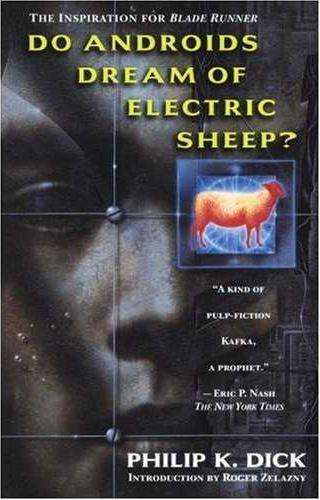

The year is 2021. Humans and androids inhabit the Earth. Artificial animals such as electric sheep can be mistaken for the real, affect-filled, offspring-bearing kind, and with the turn of a dial one’s mood can be immediately altered. This is the futuristic world created by renowned American sci-fi writer Philip K. Dick in his 1968 book “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” Here in 2008, reading a rundown copy of Dick’s book, I am perplexed about what exactly to make of it, as Dick takes us on a bold hunt for Nexus-6 androids, on the way raising questions about android rights, human authenticity and the implications of artificial life.

Dick’s main character, Rick Deckard, leads a mundane life in a San Francisco of the future with little but his wife, his Penfield mood organ, and electric sheep to entertain him. When senior bounty hunter Dave Holden is seriously harmed attempting to eliminate wanted androids, Deckard is called upon to complete the mission, a far more dangerous one than any he has ever undertaken. Deckard’s assignment consists of finding and retiring all Nexus-6 android types (think of him as an assassin, but for androids). The Nexus-6 brain unit installed in a select number of androids is far more advanced than any other created. These androids even display a far superior intelligence than some humans. If this does not pose enough of a challenge for Deckard, the androids’ exact replication of the human form and appearance, and simulation of human life, raises the level of difficulty. Deckard must also learn to keep his own emotions in check, especially when the time comes for him to eliminate an android to which he has become particularly attached, named Rachael Rosen.

A recurrent theme in Dick’s writing is the differentiation between reality and fiction. It is believed that the untimely death of Dick’s twin sister Jane, who died five weeks after her birth in 1929 in Chicago, had a strong influence on this aspect of his work. The severing of the innate connection between him and his twin sibling created in Dick a dual perspective of the world. As a result, his writing often deals with the conflicts of real versus fake and human versus android.

In “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” Dick tackles head on the issue of real versus artificial life. His main character, Deckard, must track down the Nexus-6 androids, which are aware that they are being hunted, and “retire” them as quickly and cleanly as possible. Such treatment of a form of life, artificial though it may be, begs the question as to whether androids and electric animals should be entitled to rights. Can the murder or retirement (depending on your viewpoint) of Dick’s “andys” be justified? Should androids and electric animals even be created in the first place? Are they a threat to humans? Dick seeks to answer these questions by first exploring what separates human from machine.

The primary distinction Dick makes in the book between human and android is the extent to which the subjects in question can feel and empathize. Dick puts a strong emphasis on our unique capacity to feel, to uphold morals, and to respond and connect with others on a level that often requires few words. Before the retirement of any android, Deckard must administer the Voigt-Kampff test, which is similar to the Turing test, described by Alan Turing in 1950. While the Turing test is used to detect machines based on their thinking capabilities, the Voigt-Kampff test is used to weed out human replicas based on bodily function and emotional response. Those who fail the test are simply not considered human and the authorization can be made for their elimination.

As I read Dick’s book, I found I was sympathetic towards the androids. After all, they were aware that they were being tracked down and cared enough to want to go on the run. If they feared for their lives, then is it not clear that they are capable of evoking some level of emotion? The Voigt-Kampff test may not have declared them to be human, but their capacity to sense and respond to danger does indicate that they are sentient beings. As long as beings are self-aware, regardless of how little they emote, I think they should be entitled to rights. After all, would you be able to harm someone who you knew would feel pain, either physical or emotional, as a result of your actions? I think Dick grapples with the issue of what level of feeling can be considered characteristic of humans throughout his writing.

Another important question often addressed in Dick’s work is what constitutes the “authentic human being”? Is it our capacity to blunder, recover, learn, adapt and evolve? Is it our ability to reason, desire and set goals? While Deckard dreams of owning a real-life sheep, one must wonder, do androids have wishes and aspirations? Do androids dream of owning electric animals; do they dream of electric sheep? Are their inner desires reflected in their dreams? Are they even able to stimulate thought and imagery in their unconscious state? Perhaps the existence of an unconscious mind is one of the most fundamental differentiations between real and artificial life. If intelligent machines are part of our future, all of these questions will likely need to be addressed before they can be integrated into our everyday lives.

Science fiction writers attempt to provide answers to questions regarding the implications of artificial life by creating future scenarios in which intelligent machines coexist with humans. They can be seen as modern day “oracles” as they envision advancements in technology that begin to be integrated into our everyday world. They describe scenarios we would not otherwise have imagined as we are occupied with our own daily lives and with the opportunities available in the present. Four decades ago, Philip K. Dick had imagined a time when androids and the use of mood-inducing devices, such as the Penfield mood organ, were part of everyday life. Now, such a time no longer seems so farfetched as society is constantly looking for faster and more efficient machines, even if that means blurring the line between real and artificial. “Androids,” as mentioned, was originally published in 1968, but Dick had imagined a world so far beyond his time that even today his work is as futuristic as ever. While the existence of humanoid robots seems farfetched, Dick’s work does hone in on an issue that we are forced to confront every day: our growing dependence on technology.

“Androids” has even more relevance now than it did four decades ago as our society’s reliance on computers, especially the Internet, and gadgets such as cellular phones and portable music players continues to escalate. As new technologies are constantly being developed, the gap between human and machine recedes at alarming rates. At any time of the day, we can receive services and make purchases without even leaving our homes and little to no communication is needed. Online shopping, for instance, has reduced us to beings who immediately satisfy our nearest desires with the touch of a button. While we may now be able to connect with others on a different continent, we are slowly losing touch with our immediate surroundings. The advancements made in technology over the last three decades have drastically changed our way of living and interacting with the world. After all, I would be hypocritical to allow such advancements to go unacknowledged as I am currently sitting in front of a computer writing this article. However, user-friendly programs and products can take away the sense of fulfillment of having learnt on one’s own. With the emergence of faster, more powerful, and more compact machines and devices, society has drifted down a path of laziness and over-reliance. Rather than responding to a computer and clicking on colourful icons, we should have to interact with others and work more for our needs because such interactions are important for extracting deeper meaning and greater satisfaction from life. As our interactions become more virtual, we lose our unique human capacity to connect on an emotional and spiritual level with others.

In order to keep up with our growing, fast-paced society, individuals must constantly produce new technology, further human knowledge, and push scientific boundaries at all costs. Has this growing need for maximum production resulted in the reduction of humans to machines? Are we only extracting as much use out of each other as possible? If individuals solely view one another as means to an end, one must wonder what will become of our emotional and spiritual connection with others. Conversely, we are now witnessing the development of a higher state of consciousness in machines. As society furthers its knowledge of technology, new information is implanted in machines, rendering their capabilities almost limitless. Being able to receive, process, and send information is an integral part of being human. It allows us to communicate, think critically and make rational decisions. Can it therefore be said that the information-processing abilities of machines render them more human? If so, will it be long before human and machine merge entirely?

While Dick’s work raises a number of questions as to the exact role artificial life can and will have in our future, one thing is certain, “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?” leaves little need for thought-inducing, mood-stimulating contraptions as there is no doubt that readers will turn over the last page with affected consciences and stirred minds.

Further Reading List:

I, Robot by Isaac Asimov

I-robot Poetry by Jason Christie

The Terminal Man by Michael Crichton

The Minority Report by Philip K. Dick

Comments

No comments posted yet.

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!