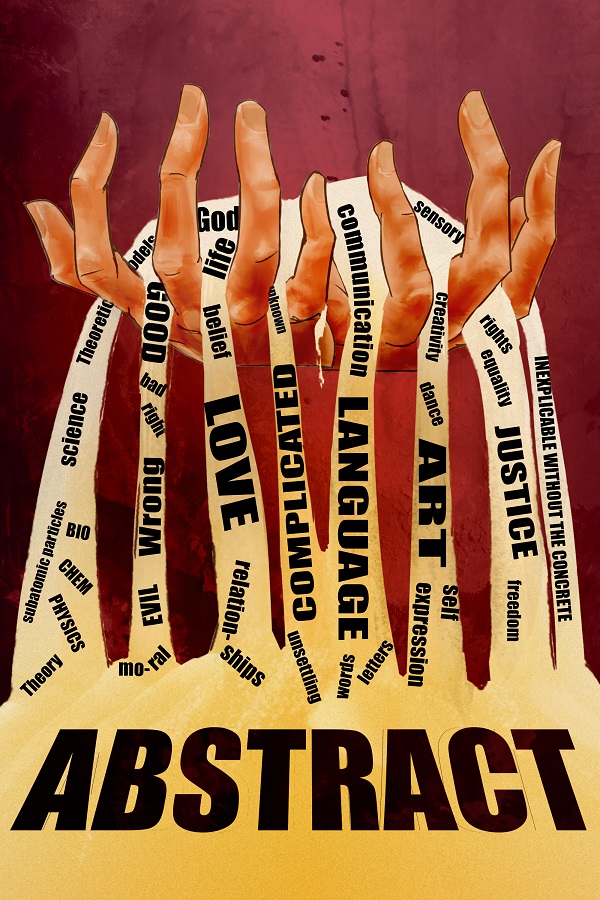

The Challenge of the Abstract

Illustrated by Alina Cara D’Amicantonio

Emily McIsaac:

Whenever I encounter something abstract, whether it’s abstract art without obvious embodiments or scientific theories describing something that can’t be seen by the human eye, the first thing I always think is: where do I even start? I think sight is generally the first of the five senses we use to understand the world around us, and seeing an image we can’t identify, or trying to visualize something beyond imagining, like an 8th dimension, can entirely confuse. Some abstract scientific models are not even observable or falsifiable with our current technology. This is why it’s so difficult for people to accept these speculative theories: humans like to have evidence, to be able to test that evidence, and so these abstract ideas and realities can definitely be overwhelming.

Julien Otis-Laperrière:

The very idea of the abstract is unsettling—it implies that our perception doesn't cover the entirety of our reality. Try to think up an abstract scent, an abstract sound, an abstract consistency (touch) or an abstract taste. It is, to me, impossible to conjure up any of those ideas, suggesting that the abstract lies beyond those senses.

Of all the senses, vision might bring us the closest to abstract realities. Throughout our lives, we have all been explained abstract ideas such as good, evil, justice, love and others mostly through visual metpahors, such as darkness and light. We can also glimpse abstract realities through their visual evidence: for example, we see a punch being thrown, we see retaliation, which are manifestations of the abstract idea of justice. But the vision remains a metaphor or a glimpse of something unseen beyond it.

The abstract is usually communicated through language. It is by talking, writing, using words like the ones mentioned above––good, evil, justice, love––that we usually discuss the abstract. Despite the fact that we cannot physically sense an abstraction, we communicate it through sounds and sights––spoken and written letters.

Gabrielle Vendette:

Your suggestion, Julien, on describing our abstract experiences through senses and words makes me think of an essay I read on trying to describing sight to a blind person. When we start trying to describe the abstract world around us, I realize how important it is that we all have a common starting ground. Imagine trying to explain the sky or the ocean to someone who has few other comparative bases. This is where the flaw in our communication about the abstract comes up; we use comparisons that most people have lived to try and explain abstract concepts, but what if someone doesn’t share the same frames of reference?

From what I remember, the person who wrote the essay suggested that we use emotions to try to describe things to the blind. For example, the sky makes me feel free, inspired, scared, etc. I find it interesting how, still, in that case, we use abstract emotional experiences to try and explain abstract sensory experiences to people.

Emily:

One abstract phenomena in our world that has been discussed again and again is love. One dictionary definition of love is: “an intense feeling of deep affection.” This definition, however, isn’t satisfactory to me. Instead of getting at the heart of love (pun intended), it seems to diminish ‘love’. In fact, when people are asked questions such as, “Why do you love him/her?” or “What do you think love is?” people often answer with stories and comparisons. Someone might say, “Love is like a warm cup of sweet tea,” since tea is widely known and associated with certain feelings. Or someone might tell the story of how they met their partner, or stories from their journey of falling in love.

Therefore, I think, when we perceive abstract or unfamiliar things, our first resort is to compare them to concrete things that are familiar to us, in order to understand them.

Chloe Sautter-Leger:

I agree with the idea that every physical thing we can possibly imagine has to be something or a combinations of things that we have once perceived. That's why I find abstract visual art can be interesting: it synthesizes parts of things we know into new combinations. These combination of shapes, colors, and textures not only do not represent anything from the world around us, but also have no function other than an aesthetic one. Other forms of abstract art—art that does not emulate nature (for example architecture or culinary art) have the function of attending to one of our fundamental needs. We manipulate and mix food to make eating more pleasant; we finely design and decorate the places we live and work in to make them more agreeable. What I find weird is the fact that for centuries and centuries in the visual arts, humans have tried to represent concrete things of the world with exactitude instead of, like with food or building materials, trying to come up with new, pleasing mixes of colors and shapes. From the over-17 000-year-old paintings of Lascaux to Brunelleschi's linear perspective, and even to impressionist art, which although it sought to focus on impressions still depicted the concrete objects from which those impressions arose, visual art has been an ‘imitation’ of nature to different degrees. Why did abstract visual art not develop before the 19th century?

Certain works of abstract visual art—my favorite are ones by Kandinsky, Arthur Dove, and Fernand Léger—are extremely pleasing to look at. When I look at the whole picture, I feel a satisfaction that the disunited, cacophonic pieces somehow fit well into the whole (usually rectangular) space of the work. The work of art thus stands for itself, as it does not represent anything concrete from outside of it, except for colors, textures, and shape.

Music has always been abstract (especially music without words—but then again, words themselves, even if they represent concrete things, are also abstract); and so has dance, so I really wonder why it took so much time for people to truly appreciate the power of visual abstract art as something aesthetically pleasing and possibly emotionally inspiring.

Emily:

In response to Chloe about abstract art: I also find the recent esteem for abstract art very intriguing. It’s possible that abstract art has existed for a long time, but it has only been explored and accepted recently. Or, since it is widely thought that the largest human fear is the fear of the unknown, and since abstract art does not represent concrete realities and truths, but “unknown” ones, it can be unsettling. Therefore, I think it took open modernist views for people to deeply explore the abstract.

The emergence of abstract art is seen not only in paintings, drawings, and sculptures, but also in photography. My favorite periods in photography are American straight photography and the early 20th century European avant-garde photography, where different styles were explored and photographers re-evaluated what photos can depict. Man Ray and Edward Weston are two of my favorites.

Ross:

A theory that deals with the abstract that I find incredibly interesting is Taoism.

The eastern philosophy of Taoism states that our reality is composed of Tao, which is the source of our existence and yet does not possess any physical being, nor is it some kind of God. The Tao Te Ching, fundamental Tao text, begins with "The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao.” In other words, we cannot describe what the Tao is through language; we can only feel the Tao in its effects on the world around us. For example, Tao is present within a running river flowing downstream, or a gust of wind, and it is also responsible for the very essence which makes us human beings.

I find this kind of thinking is both incredibly interesting and frustrating. A source of life is around us, and yet, we cannot understand or communicate it.

Chloe:

What you brought up about Tao is very interesting, Ross. Many religions and philosophies revolve around some concept of a One 'thing' that exists beyond anything we can imagine or describe. The Zhuangzi says that "the Way is to man as rivers and lakes are to fish, the natural condition of life.” It is somehow all-encompassing, omnipresent, but we do not understand it.

In some way, as you find, Ross, this is frustrating. But I think this concept might be there because we encounter things in life that we simply cannot explain, either because we don’t understand how they happen or because we don't know any words that have been invented in our language that can describe the exact feelings we are feeling. Out of these unexplainable (abstract) irrational moments, we can develop a belief in something like Tao.

Some things are more obviously unexplainable than others, but I wonder if any emotion can ever perfectly be described. We have hundreds of words to describe our emotions; we learn to use these words by experiencing many of these abstract emotions, for example by being 'irritated' many times, and then we understand what these moments have in common. But I don't think that our emotions are ever exactly the same. They are each time so complex that even the abstractions we have—our words—cannot describe them precisely.

I think recurring dreams are one of these things that we associate with each other, even though we can't always put words on them and can never describe them exactly. I find the fleeting memory of dreams a fascinating phenomenon that might offer a glimpse of the abstract.

Comments

No comments posted yet.

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!