Women’s Religious Autonomy in Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper

Sister Plautilla Nelli (1524-1588) is one of the earliest documented Florentine women Renaissance painters. Though nuns were expected to be cloistered and isolated, she was respected during her lifetime; her artworks were owned by many local noblemen (Garrard 42), and she is even mentioned in Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Artists (Hayum 248).

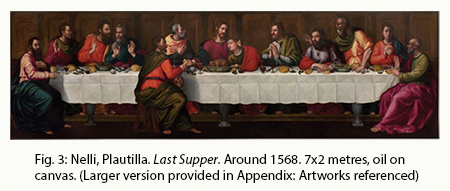

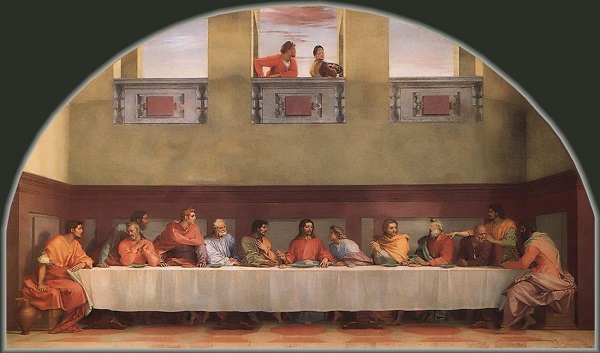

Perhaps her most notable work is her 7x2 metre oil on canvas Last Supper, painted around 1568. Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper exhibits a physicality that celebrates the autonomous religious practice of the nuns at the Santa Caterina abbey and that applies the theology of their patron Saint Catherine of Siena. Compared to two paintings by male artists from whom Nelli may have drawn inspiration, her Last Supper uniquely emphasizes Christ’s physical humanity, linking him to the nuns eating in the refectory in which the painting hung.

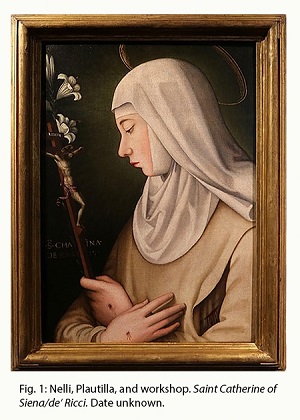

Saint Catherine’s importance in Nelli’s oeuvre is apparent; a number of Nelli’s paintings show Saint Catherine in the midst of one of her most famous visions, stigmata appearing on her hands and side as she holds a flowering crucifix with a detailed miniature Christ (Fig. 1; Navarro 79, 85). In my summation of Catherine of Sienna’s life and mysticism, I will draw from Caroline Walker Bynum’s 1987 book Holy Feast and Holy Fast, which presented an influential new narrative regarding the food practices of late-medieval women, among them Catherine of Siena.

The fourteenth century mystic began refusing food in her childhood, and she clashed with her family over her ascetic practices and her refusal to marry. She would “shove twigs down her throat to bring up the food she could not bear to have in her stomach” (Bynum 168). Eventually, she could only subsist on the Eucharist. Communion would sometimes trigger intense visions. Extreme religious practice was, by the late Middle Ages, seen as dangerous for women due to their supposed weakness. This fear also effectively marginalized women from religion. However, Catherine of Siena found autonomy in extreme religious practice, first avoiding marriage thanks to her extreme asceticism and eventually becoming an influential religious figure (Bynum 165-80).

throat to bring up the food she could not bear to have in her stomach” (Bynum 168). Eventually, she could only subsist on the Eucharist. Communion would sometimes trigger intense visions. Extreme religious practice was, by the late Middle Ages, seen as dangerous for women due to their supposed weakness. This fear also effectively marginalized women from religion. However, Catherine of Siena found autonomy in extreme religious practice, first avoiding marriage thanks to her extreme asceticism and eventually becoming an influential religious figure (Bynum 165-80).

Many of her miracles were related to food. She provided food to the hungry and poor, made mothers’ breasts run with milk again, and even “diagnosed a possessed man as needing food” (Bynum 170). Her role as a provider of food was both Christlike and maternal. Her biographer writes that “She truly was a mother to us, who continually gave birth to us from the uterus of her mind, enduring for us the groans and pangs of labor and fed us assiduously on the bread of sound and saving doctrine” (Bynum 171). The image of simultaneously spiritual and physical motherly healing appears throughout her visions and miracles. She had visions of drinking from the stigmata at Christ’s breast, drawing milk and/or blood from him like a child with their mother (Bynum 165-80).

In Chapter 9, Bynum argues that the association of physicality with both Christ’s humanity and with womanhood created the connection many women had with food and fasting. Women were seen as weak, physical, and fleshy, but this linked them to Christ, as he was fully human. Moreover, “the flesh Christ put on was in some sense female, because it was his mother’s” (Bynum 265). Food provision, seen as the domain of women, mothers in particular, was also the role of Christ each time someone consumed the Eucharist. Effectively, Saint Catherine appropriated misogynistic Church doctrine to create a space for women’s spirituality. Her feminized physicality and weakness was part of her humanity, bringing her closer to Christ and providing a consistent reason for being involved in public and religious life despite being a woman.

Given Bynum’s analysis of Saint Catherine’s mysticism, it is already apparent why the depiction of the Last Supper was significant at the convent that bore her name. The Eucharist tradition comes from the gospel account of Jesus saying that the bread on the table was his body, and the cup of wine was his blood. A more in-depth analysis reveals that Nelli created an intensely physical Last Supper that validated the women’s religious community she painted it for.

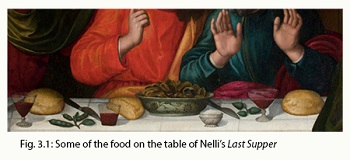

Nelli’s stylistic choices are made apparent by comparing her painting to other Florentine convent Last Suppers that may have influenced her. Both Pietro Perugino and Andrea del Sarto are known influences on Nelli’s Lamentation (Garrard 11). Their Last Suppers in the Fuligno (Fig. 5, 1493-1496) and San Salvi (Fig. 4, 1526-1527) refectories are an excellent example of the model which Nelli adapted. The food looks flat and insubstantial compared to Nelli’s rich and colourful spread. In her essay on “Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper and the Tradition of Dominican Refectory Decorations,” Ann Roberts shows how the meal reflected convent life (Strocchia). The table includes meat, loafs of bread, cups of red wine, salt cellars, greens, and even a Florentine bean dish (Fig. 3.1). The bountiful spread represents the spiritual nourishment Catherine envisioned in Christ. In acknowledgment of Christ’s full humanity, the table bears the God-granted physical nourishment of the

Nelli’s stylistic choices are made apparent by comparing her painting to other Florentine convent Last Suppers that may have influenced her. Both Pietro Perugino and Andrea del Sarto are known influences on Nelli’s Lamentation (Garrard 11). Their Last Suppers in the Fuligno (Fig. 5, 1493-1496) and San Salvi (Fig. 4, 1526-1527) refectories are an excellent example of the model which Nelli adapted. The food looks flat and insubstantial compared to Nelli’s rich and colourful spread. In her essay on “Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper and the Tradition of Dominican Refectory Decorations,” Ann Roberts shows how the meal reflected convent life (Strocchia). The table includes meat, loafs of bread, cups of red wine, salt cellars, greens, and even a Florentine bean dish (Fig. 3.1). The bountiful spread represents the spiritual nourishment Catherine envisioned in Christ. In acknowledgment of Christ’s full humanity, the table bears the God-granted physical nourishment of the Eucharist, and even of more secular foodstuffs. Saint Catherine was an active provider of food to her community, so mundane dishes, such as the local bean dish, are also worth representing. The daily convent meal is made into a spiritual experience, since it is a participation in the humanity that makes the nuns Christlike and a celebration of the earthly gifts provided by God and his representatives, including St. Catherine.

Eucharist, and even of more secular foodstuffs. Saint Catherine was an active provider of food to her community, so mundane dishes, such as the local bean dish, are also worth representing. The daily convent meal is made into a spiritual experience, since it is a participation in the humanity that makes the nuns Christlike and a celebration of the earthly gifts provided by God and his representatives, including St. Catherine.

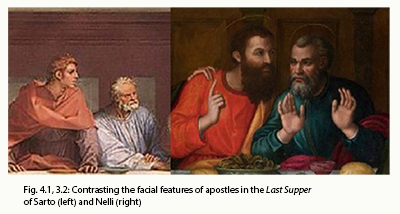

Her influences chose soft blues, yellows, and greens. Nelli’s greens are darker, and rich reds and bright oranges draw the eye. Her backdrop is heavy brown wood, rather than palatial plaster or stone. There is no vaulted ceiling or wide open windows, and her apostles crowd the table, emphasizing their physical presence. They even look fleshier, with round faces, thick beards, and rosy cheeks.  She paints darker skin tones associated with semitic origins of physical connotation, rather than the obviously hellenized facial features that are particularly noticeable in the Sarto (Fig. 4.1).

She paints darker skin tones associated with semitic origins of physical connotation, rather than the obviously hellenized facial features that are particularly noticeable in the Sarto (Fig. 4.1).

Typically, the subject draws a contrast between the devilish Judas, associated with the worldly and base, and the divine Christ and pure John (Polzer 16). The Last Supper’s physicality in Nelli’s hands transforms this dichotomy into a paradox by emphasizing that Christ was also human and physical (although undermining this is the fact that in keeping with tradition, Judas sits opposite to Christ and is the darkest-skinned of anyone at the table). Instead of a contemplative celebration of Christ’s divinity at the Last Supper, Nelli presents a physical celebration of Christ’s humanity that makes him not only like the apostles, but like the nuns eating in the refectory. Nelli reflects St. Catherine’s theology by presenting a model for female spirituality that appropriates the physicality associated with women and used to marginalize them from religion.

In an essay on Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper (1445-1450) in the refectory of the convent of Sant’Apollonia, Andrée Hayum makes some interesting points worth considering with Nelli’s take on the subject. Hayum argues that the sharp masculinity of Jesus and the apostles in Castagno’s painting represents “the exempla for female piety, […] virility as a safeguard to faith” (Hayum 251). Castagno’s painting is a didactic lesson about defending virginity and piety as is necessary both internally, through “masculine” self-control, and externally, through the enclosure of nuns within their convent (Hayum 252). Hayum acknowledges the misogyny of the implied danger of women left unchecked (Hayum 253), but points to John, who is centred in the painting, as a symbol of youthful purity and virginity nuns could aspire to (Hayum 256). The masculine apostles and enclosed convent protect “him”.

Castagno’s painting is dated over a century before Nelli’s, and I do not know whether she would have known of it. However, the masculine apostles and youthful virgin John also appear in Sarto’s and Perugino’s Last Suppers, showing that nuns should control themselves and be controlled. John is similarly virginal in the Santa Caterina painting, but his context is very different. Nelli’s feminine men have sometimes been seen as an artistic limitation, but in this case, they work to enhance Saint Catherine’s mysticism. Christ is rosy-cheeked and maternal. Unlike Sarto’s or Perugino’s John, Nelli’s John is held directly to Christ’s bosom, as is described in the gospel of John (Fig. 3.3; John 13:23 KJV). Saint Catherine’s image of being held to drink from  Christ’s stigmata like a baby at the breast is evoked, particularly because of the Eucharistic connotations of the Last Supper. Saint Catherine even exemplified the religious piety and virginity that John represents, and would likewise have been a model for nuns.

Christ’s stigmata like a baby at the breast is evoked, particularly because of the Eucharistic connotations of the Last Supper. Saint Catherine even exemplified the religious piety and virginity that John represents, and would likewise have been a model for nuns.

Nelli’s bountiful table celebrates Saint Catherine’s influential mysticism: religiosity “to excess” as accessed through the physical self. Placing a feminized John next to a feminized Jesus emphasizes this even further. The space is physical and female, without imposed notions of masculinized restraint.

An entirely new essay could be written to fully capture the significance of this celebration of autonomous women’s spirituality in post-Savonarolan Florence, but a brief summary will have to do, as outlined by Mary Garrard in her article “The Cloister and the Square”. The convent of Santa Caterina was founded in 1496 by a disciple of the preacher Savonarola. Savonarola had many women followers, and at first offered them “an unprecedented voice in religious reform” (Garrard 23). He withdrew the proposal after backlash, however, and the Savonarolan monks of San Marco increased their control over Savonarolan convents for many years after his death.

Across Florence, after the death of Savonarola, religious women were increasingly feared and limited. Saint Catherine of Siena appeared in visions and became a symbol to some women who continued to struggle for religious autonomy, such as Suor Domenica del Paradiso (1473-1553) (Polizzotto 506). Plautilla Nelli watched as “convent walls were built higher, windows sealed up and veiled” (Garrard 37). In her invocation of Saint Catherine’s mysticism, she resisted this marginalization by presenting to the nuns of her convent an image of the women’s space they inhabited and the connection of women, through their humanity, to the divine.

Works Cited

Bynum, Caroline Walker. Holy Feast and Holy Fast : The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women. University of California Press, 1987. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=40049&site=eds-live&scope=site. Accessed 8 May 2020.

Garrard, Mary D. “The Cloister and the Square: Gender Dynamics in Renaissance Florence.” Early Modern Women, vol. 11, no. 1, 2016, pp. 5–44. JSTOR, [url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/26431438]http://www.jstor.org/stable/26431438[/url]. Accessed 7 Mar. 2020.

Hayum, Andrée. “A Renaissance Audience Considered: The Nuns at S. Apollonia and Castagno's ‘Last Supper.’” The Art Bulletin, vol. 88, no. 2, 2006, pp. 243–266. JSTOR, [url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067244]http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067244[/url]. Accessed 8 Mar. 2020.

Hoerr, Caitlin. “‘The Word Gave Himself as Food’: Female Piety and Food in Italian Renaissance Art.” American University, 2015.

Lorenzo Polizzotto. “When Saints Fall Out: Women and the Savonarolan Reform in Early Sixteenth-Century Florence.” Renaissance Quarterly, vol. 46, no. 3, 1993, p. 486-525. EBSCOhost, doi:10.2307/3039103. Accessed 11 May 2020.

Navarro, Fausta (Editor). Plautilla Nelli: Art and Devotion in Savonarola’s Footsteps. Exhibition Catalog. Uffizzi Gallery. 2017.

Nelli, Plautilla. Last Supper. Around 1568. Museum of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. Accessed through Jessica Stewart. “16th-Century Nun’s Incredible ‘Last Supper’ is Restored by an All-Female Team of Experts.” My Modern Met, 20 January 2020, mymodernmet.com/plautilla-nelli-last-supper/. Accessed 8 March 2020.

Perugino, Pietro. Last Supper. 1493-1496. Cenacolo di Fuligno, Florence. The Museums of Florence, www.museumsinflorence.com/musei/fuligno_last_supper.html#. Accessed 8 March 2020.

Polzer, Joseph. “Reflections on Leonardo’s ‘Last Supper’.” Artibus et Historiae, vol. 32, no. 63 (2011), pp. 9-37. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41479735. Accessed 10 May 2020.

Rigaux, Dominique. “The Franciscan Tertiaries at the Convent of Sant'Anna at Foligno.” Gesta, vol. 31, no. 2, 1992, pp. 92–98. JSTOR, [url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/767042]http://www.jstor.org/stable/767042[/url]. Accessed 10 Mar. 2020.

Roberts, Ann. “Plautilla Nelli’s Last Supper and the Tradition of Dominican Refectory Decorations.” Suor Plautilla Nelli (1523-1588): the First Woman Painter of Florence, by Jonathan Katz Nelson, Cadmo, 2000.

Sarto, Andrea del. Last Supper. 1526-1527. Cenacolo di San Salvi, Florence. The Museums of Florence, www.museumsinflorence.com/musei/san_salvi_last_supper.html#. Accessed 8 March 2020.

Strocchia, Sharon T. “Review: Suor Plautilla Nelli (1523–1588): The First Woman Painter of Florence, by Jonathan Nelson”. CAA Reviews, 2000. DOI: 10.3202/caa.reviews.2000.121. Accessed 11 May 2020.

Artworks Referenced

Fig. 1: Nelli, Plautilla. Saint Catherine of Siena.1550s. Uffizi Gallery, Florence. 18x14 centimetres, oil on copper.

Fig. 2: Nelli, Plautilla, and workshop. Saint Catherine of Siena/de’ Ricci. Date unknown. Museum of the Cenacolo of Andrea del Sarto, Florence. 38x28 centimetres, oil on panel.

Fig. 3: Nelli, Plautilla. Last Supper. Around 1568. Museum of Santa Maria Novella, Florence. 7x2 metres, oil on canvas.

Fig. 4: Sarto, Andrea del. Last Supper. 1526-1527. Cenacolo di San Salvi, Florence. 525x871 centimetres, fresco

.

.

Fig. 5: Perugino, Pietro. Last Supper. 1493-1496. Cenacolo di Fuligino, Florence. 4.4x8 metres, fresco.

Fig. 6: Castagno, Andrea del. Last Supper. 1445-1450. Sant'Aplollonia, Florence. 453x975 centimetres, fresco.

Comments

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!