Shell-Shocked

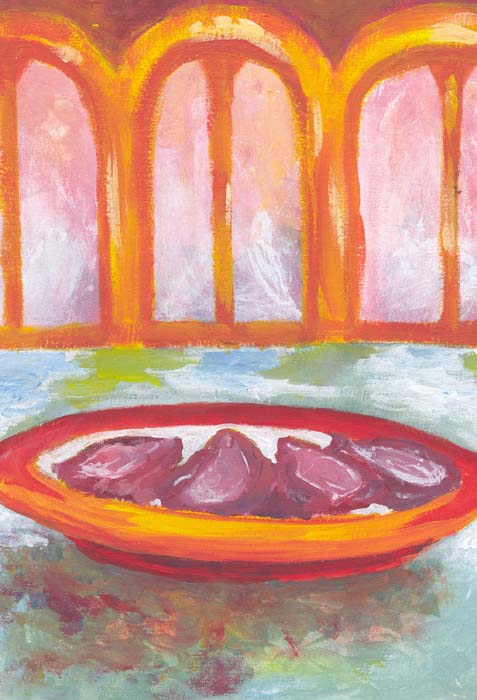

Illustrated by Caitlann Allan and Paule Racicot

We live in a world where there is little separating an oyster from a rock.

I did not always live in this world. I used to live in a world where mermaids lurked beneath the ocean depths, where one island was the centre of the universe and oysters were commodities instead of pearls.

Growing up on an island by the sea-side, near a beach covered in the not-so-picture-perfect remnants of social media escapades, the closest I ever found myself to what I considered the true essence of the ocean was through food. I dreamt of mermaids and sunken kingdoms at night, but when I woke to harsh reality of morning I found myself nearer to my imaginary adventures through fishermen and street food stalls than through wading in tumultuous Sri Lankan waters.

On the island, seafood was an unavoidable consequence (an allergy would basically bring shame to both your honour and that of your family’s). In contrast, many of my Canadian friends do not hesitate to voice their disregard for the merits of my people's bounty. These naysayers claim that they could not possibly stomach the taste of seafood because it is ‘fishy’ and at that I scoff (only somewhat pretentiously). ‘Fishy’ in my opinion is the adjective of someone who has never lived near the ocean, of someone who has not tasted the ambrosia that is a sea creature plucked straight from ocean and placed delicately onto their plate.

On the island, seafood was an unavoidable consequence (an allergy would basically bring shame to both your honour and that of your family’s). In contrast, many of my Canadian friends do not hesitate to voice their disregard for the merits of my people's bounty. These naysayers claim that they could not possibly stomach the taste of seafood because it is ‘fishy’ and at that I scoff (only somewhat pretentiously). ‘Fishy’ in my opinion is the adjective of someone who has never lived near the ocean, of someone who has not tasted the ambrosia that is a sea creature plucked straight from ocean and placed delicately onto their plate.

Fish served as it is meant to be served (within hours of being caught) has a clean flavour, like meat without blood. Most seafood tastes pristine, pure and delicate as a jasmine flower’s scent. European favourites like cuttlefish melt in your mouth like sweet butter, its flesh putting up little resistance against your molars, while the traditional Asiatic choice of snapper roe coats your tongue in a tender symphony of umami, savoury juices submerging your consciousness in gustatory delight.

Yet, out of all the beautiful and delicious sea creatures I have had the pleasure of relishing, nothing comes quite close to the debris-encrusted container of ocean nectar that is the oyster. The overriding flavour of an oyster is that of salt, but it remains a flavour-profile that cannot simply be replicated with any run-of-the-mill shaker of clumped white grains. Oysters contain unique pockets of salty and mildly saccharine liquid, infused naturally with the ever-elusive umami that most dishes seek to introduce through the addition of reduced stocks and aromatics. An oyster is essentially a flavour bomb, releasing a refreshingly savoury concoction as you simultaneously swallow and bite its slippery flesh. Now, imagine this flavour slightly enhanced; a squeeze of lime adds a tang that electrifies your taste buds and a dash of hot sauce stimulates a quivering warmth that melds harmoniously into both the zest of the citrus and the pleasurable sting of sea salt. As a child, this was enough to make the oyster the embodiment of the ocean’s merits in my eyes.

After having moved to Canada (and leaving behind easy access to fresh-shucked oysters in the process), I struggled with the abrupt disconnection I felt in the midst of maple syrup lakes and poutine mountains. Sri Lankan food had been my life, every memory captured in some part by whatever I had ingested throughout my childhood. Seafood had been my vice and a symbol of every good time I had enjoyed in the company of friends and family as we watched the waves lap against worn rocks or competed in building transient sand-castles. When I moved to a country where natural flavour was almost completely discarded in favour of more wallet-friendly options, I observed that other children were driven to the point of fanaticism by the sight of ready-made goods such as fluorescent cupcakes and flatbreads smothered in tomato sauce and cheese.

My parents probably assimilated faster than me, as they were no longer quick to offer me the oceanic fruits I had revelled in during the first half of my lifetime, instead shoving crisps and candy in my direction as some form of hasty distraction. Suddenly, oysters were like pearl necklaces: a luxury my parents could not afford.

My next meaningful encounter with oysters came several years after I had first moved to Canada. As I got older, my eye had become drawn into the culinary world in a way it had not been before. Now, I cooked to satisfy my hunger. Flavour had morphed into something beyond what existed either in the realm of pleasant and unpleasant; it had depth, countless layers working both individually and cooperatively to create an experience that transcended nostalgia. I joined a cooking club lead by a veteran cook, whom I militaristically addressed as “Chef” despite often being asked to refer to him (in what I saw as a wholly unprofessional manner) as “Danny”.

Chef, whose light-hearted banter warmed up even the coldest of his students and whose debate was fierce enough to rival any open flame, taught me almost everything I know about cooking. Most importantly (for this story’s sake), he re-introduced into my life the magical crustaceans that are oysters.

One cool, autumn evening, Chef hauled into the kitchen a wooden crate lined with newspaper and filled to the brim with a variety of aquatic produce. Filets of cod wrapped in parchment rested against bundles of gleaming dark mussels and chalky clams, while the star of the show, a small bucket of ribbed, dirty oyster shells, perched prominently atop the lesser denizens of the crate.

One cool, autumn evening, Chef hauled into the kitchen a wooden crate lined with newspaper and filled to the brim with a variety of aquatic produce. Filets of cod wrapped in parchment rested against bundles of gleaming dark mussels and chalky clams, while the star of the show, a small bucket of ribbed, dirty oyster shells, perched prominently atop the lesser denizens of the crate.

I had never shucked an oyster before, but I presumed the task at hand would be relativity easy. To write that I misjudged my abilities or, at the very least, the complexity of the maneuver would be an understatement.

Leading up to that day, my experience with oysters had been limited to the ingestion of the prepared creature, shucked into half-shell, cleaned, and presented artfully on a bed of densely packed salt like fruit ripe for the picking. Never before had I been forced to confront an oyster in its most primal state, clamped tightly in fear and covered in grime-encrusted, sharp barnacles and ridges.

Chef made it look easy as he took apart the creature into a familiar form. He roughly washed the crustacean in cold water, before grabbing an oyster shucking knife in his other hand and placing its tip into the base of the oyster’s shell hinge. He wrenched the knife into the hinge, twisting the tip of the blade as far into the narrow space as possible before levering the knife upwards. The hinge was pried open with a pop, but the shell did not give way just yet. He continued to slide the knife under the top shell, scraping apart the singular tendon still holding the flat top shell to the oyster’s basin-like bottom shell. Finally, he revealed the delicious creature lying beneath, immersed in a transparent fluid.

My own first attempt at performing the same task was met with ill-success. I broke part of the top shell in my effort to pry it open, unveiling an oyster covered in debris from my mishap. I tried optimistically to eat it, but found, unsurprisingly, that the delicate flavour was overshadowed by the gloom of my failure as shards of oyster shell and barnacle scraped my teeth. Chef took pity on me and gave me another chance at producing the same gorgeous product as his, but this time my hand slipped, allowing precious savoury liquid to trickle out of the opening in the shell. The result was good, but nowhere as great as it would have been if some of the oyster’s flavour-defining liquid would have been retained. In the end, it took me several more tries and multiple cuts and blisters before I was able to obtain an oyster even slightly similar in quality to those I had enjoyed so frivolously in my childhood.

When I was a child, I had fallen prey to the common misconception that the oyster is delicious by mere virtue of existence. The fact of the matter is that the only thing actually separating an oyster from any other rock at the bottom of the ocean in terms of taste is technique. Technique is what allows a chef or even a fisherman to effectively open an oyster, to elevate something which can be quickly underestimated into a delicacy valued as a luxury.

There is, in fact, a reason as to why the ready-made goods we are so quick to eat in this day and age do not fulfil us in the same way a home-cooked meal does, and that reason is that it lacks the care and love transmitted through the technique that is applied to a meal. Human effort is technique, which is infinitely more magical than that of a machine because it requires thought and emotion.

I never realized as a child that the creature I was relishing, although born from the sea, had been nurtured by a person into becoming the substance towards which I accorded so much value. I bled and (embarrassingly enough) cried in order to achieve what I considered a beautiful oyster on the half-shell and I was all the more proud of my creation because of it. During the time when I lived in my childhood fantasy world, I had not yet understood that behind every amazing facet of life and of food that there is technique, which is the pain-staking process, skill and practice which combine to allow mediocre objects to turn into art.

Comments

Mark David Alejandro

September 1, 2020I enjoyed reading this piece. The story of a girl’s childhood from Sri Lankan Waters who enjoys eating seafood (especially oysters) until she moved to Canada was very well explained in this piece. Seafoods are mostly the food she was raised with and it is also the main the dish that can be offered to her by her family. I enjoyed reading this piece because I can relate to the girl’s story. Our province in the Philippines is an island by the sea-side just like where the girl lived in the Sri Lankan waters. I love how she was thought to prepare an oyster by her chef when way back her childhood she thought that what they caught in the sea was simply it she didn’t know that there was an effort which is the human technique that she later on learned as she grew older. “I used to live in a world where mermaids lurked beneath the ocean depths, where one island was the centre of the universe and oysters were commodities instead of pearls” I found this section interesting because these past few days I really enjoyed watching mermaid series, movies, everything about mermaids.

Beatrice Millie Rocheleau

September 2, 2020I adored reading this piece as I felt it was particularly drawn to me. As a child, I was privileged enough to be fed seafood, the whole spectrum of it, and I adored every single bite. But as strange as it sounds, at around seven years old, I developed an intolerance to all seafoods : anything that comes from the sea, I cannot eat anymore. This piece brought my inner mermaid back to life. I didn’t feel any discomfort reading through the details of how oysters are carefully prepared, in fact I was paying close-up attention to every single word. I was reading this piece with some sort of 3rd-party passion : although I could not be excited at the imaginable sight of oysters, I could feel excited for whoever gets to enjoy such a delicacy. My mom has always taught me that it’s alright not to like a certain food, but to never abhor it. Anyway, I doubt that I will go back out in the world with my love for seafood being magically resucitated, but I’m certainly reminded that all foods exhibit beauty through effort and thought. On this note, I particularly liked the last paragraph as it explained that the true difference between outdoor food and homemade food, is found within the hands that prepare it.

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!