Renaissance Woman

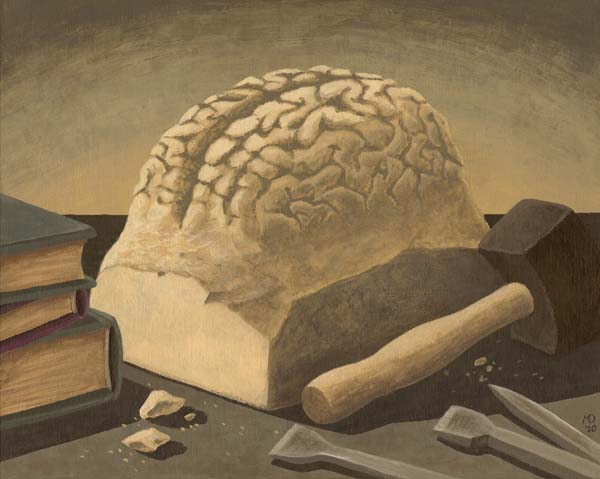

Illustrations by Mathieu Deroy (top) and Yu Ji Li (bottom)

The following interview was conducted by Anouk Arseneau with Dawson College History Professor Gesche Peters.

Q: Can you present yourself and your background as a history professor?

Q: Can you present yourself and your background as a history professor?

A: I am a history teacher in the history department at Dawson. We are all expected to be rather flexible in what we teach, so the training background with which a person came here is not necessarily what they end up teaching, and therefore, in view of the theme of TECHNIQUE as such, it is certainly very important to be versatile in approaches. Each of our backgrounds usually involves a training methodology, training in research approaches that in general are quite specific. Is it archival research? Does the research involve original documents? Do researchers have to travel? Does the research involve oral history? All of those are quite different approaches. And so, we try to obviously transfer our best techniques forwards into whatever it is that we are teaching or into how we are teaching. But everybody is expected to be flexible and therefore to be appreciative of different approaches. Also, to add to that, all history teachers are expected to teach in the methodologies. So, that automatically means you have to be familiar with approaches, methods, methodologies of the social sciences from a general level to quite a sophisticated one because that is what you are expected to teach.

Q: You also teach History of Science. Some would say that the techniques used in the sciences and in laboratory work is quite different than those used in the humanities? Since your class joins the two, what do you think about the differences and similarities between the techniques used in the sciences and those used in the humanities?

A: The techniques are really quite different, but very often, at the level at least of conveying the knowledge that you gain in those disciplines, they are quite artificially different. Obviously there needs to be quite a specific approach in the laboratory; it is a controlled environment. You in fact try to reduce all sorts of outside influences down to the manageable variable that you wish to study. So, that is really unnatural in many ways. It is designed to gain knowledge on the natural world or on natural phenomena, but the environment itself is by definition unnatural. In the humanities, the social sciences, it is exactly the opposite. It is virtually impossible to regulate all the variable that one studies. It is looking at an insanely intricate and complex system always. We are trying to make sense of those systems, see the patterns, rather than the very particulars. So, to combine the two is incredibly challenging, but also incredibly instructive, because I think certainly in the way modern education functions, people are forced at a very young age to choose a path and then of course it is important to go down that path to deepen your knowledge in that area. But unfortunately that also means that those paths shall never meet again, apparently. So, I appreciate both approaches. I can see value in both approaches, and I think everybody should make it their business to be mindful of why the approaches are different. They’re not qualitatively different; they are different because different subjects need to be addressed in a particular setting. But that knowledge in my mind is never complete unless you can also convey to the other side, so to speak, why such knowledge is important. Not just how it’s obtained, but why it’s important, because in the end it’s all a social project. And that makes them both really important.

Q: Is there a technique that you think you have mastered in your life? Whether it be in teaching or in work outside of school?

Q: Is there a technique that you think you have mastered in your life? Whether it be in teaching or in work outside of school?

A: I think right now what I have mastered by virtue of zillions of hours of practice is editing. Sheer hours and hours and hours of reading, reviewing, needing to know about everything from grammar to what the subject is that is being researched—that is quite the learning curve. And in fact it’s never finished.

Q: Is there a technique that you would like to master?

A: I would like to catch up on and gain a deeper understanding of some of the more profound methods in the sciences. My background in math is very shoddy, and at the time I thought; fine, I’m good at other things, I don’t need that really. But I have real regrets that I didn’t find it more interesting, and that my teachers could not make it more interesting for me, because I think a numerical literacy is very profound in our world. And it is not the numbering itself; it is the approach, the pure abstraction that, in my world, was dismissed, and I am as guilty of that as many other people. I think that’s something I’d really like to catch up on. As a good renaissance women, very auto-didactically, I’ve been working on this very hard, but it’s frustrating to do that because I find I’m missing part of language, or I know words but not the conjugation or the syntax of how it should function, and therefore I always feel something eludes me. But, then again, in my little social science arrogance, I can also testify that the same is true for scientists. Of all the conferences that I’ve participated in, of all the lectures that I’ve heard, and so on, in my effort to educate myself more, I am totally aware of how they’re caught in the same trap. The downright inability, sometimes, of people to explain clearly what they’re doing, why they’re doing it and why anyone should care has been astonishing. They have built their own defense system with downright arrogance by stating that what they do is somehow superior or it’s so dramatically different that if you are not in the in-club, so to speak, you don’t need to worry and you won’t gain admission. Well, the opposite is true of teachers on the social science side who reject that and say, “Well, this is just technical trap, and they’re missing the big picture.” So, I am very aware of both sides and their shortcomings.

A: Don’t you think this is the case in every area? For example, in the fine arts world, it used to be accessible to everyone before, and everyone knew about the big artists, and now no one really knows what’s going on.

Q:Yes. Absolutely, I think that’s absolutely true. But this is part of what a general specialization is in life. That’s true in business, that is true in culture, that’s true in sports.

Q: Do you think everyone should get a broader education then?

A: A much broader education. When it comes down to education, you have to be respectful of someone’s opinion, but it has to be an opinion based on knowledge, on facts, on obtained information, not opinionizing or taking shortcuts. In writing, that’s the same; you have to always be mindful that there are things that you don’t know. And it’s actually ok not to have to know everything, but to be able to rely on people who may have more expertise in an area, but then the onus in on them to be able to convey their knowledge and information as well. The learner’s obligation is always to try to go deeper based on need, or inclination, or just curiosity, but the onus in on the expert to be able to pitch their information at different levels so that there is greater communication right across the board. In art, that’s absolutely true, in physical culture, in music, which, depending on how one sees it, can be part of the arts, but musical knowledge is actually really profound, all kinds of studies show that very clearly. And yet it is art and music and drama that is the first that goes on the chopping block. There is a great emphasis on science and technical expertise, that’s where the jobs are, understandably so, but I’m very old fashioned in believing that you really have to be just a well-rounded person in order to be successful at anything, and that requires not just learning about different disciplines, or domains, but also learning more deeply in them, and that includes appreciating why their methods are different, what their techniques are first of all, why they are the way they are, and then at least trying to gather some aspects of that and starting to own them. You can only start to own something when you practice it. If you never practice it, even for the smartest person, some ideas just flash past you. It might be interesting, you take a little bit out of it, but it doesn’t go deep. And mastering techniques, one’s own and those in other domains, is a lifelong, difficult process. So the more you’re exposed, and the more you’re encouraged to engage in that in meaningful ways, the better.

Comments

Codes

September 2, 2020I absolutely agree about the arrogance that is so often synonymous with the prevalent isolation-mentality in the Sciences! As a science student myself I find myself in situations where I am being taught by teachers who despite having doctorates in their field, are absolutely terrible at explaining what they know. It’s absolutely tragic to see it in fact, it’s nearly like some of them have have some form of self-imposed aphasia! They can say so much with nevwr actually saying anything because while they know plenty about their field, they either get to the point too quickly or get off topic entirely to rant about some aspect that we have no reason to care about. It’s a bit despairing really, since the arrogance usually comes in the form of writing off anyone who learns in a neuro-divergent way, or believing that if a student does not ubderstand then it is entirely the rweult of not enough work and focus on the student’s part rather than their own shortcomings. As someone who has spent quite a while teaching myself with online classes and textbooks rather than wasting time in lectures, I find myself rather resentful of the idea that my non-science classes are somehow ‘easier’ (which is a view that goes beyond that of the in-crowd within Sciences, I’ve heard from virtually everyone) because clearly, if Humanities or a language course was so ‘easy’ they would probably be better at teaching and being open-minded to other methods and different learning styles. With that said, practice is still key, at least that much is true in every field!

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!