Reflective Response: Arts of One World

The first piece I would like to discuss is my favourite in the exhibit, The Goddess of Love, created in 2012 by artist Romuald Hazoumè. Born in 1962 in Porto-Novo, Benin (Hazoumè, wall text) Hazoumè is a multi-disciplinary artist who works with recycled materials.

The first piece I would like to discuss is my favourite in the exhibit, The Goddess of Love, created in 2012 by artist Romuald Hazoumè. Born in 1962 in Porto-Novo, Benin (Hazoumè, wall text) Hazoumè is a multi-disciplinary artist who works with recycled materials.

The upper portion of the statue, sculpted in wood, depicts a female torso and head. Although her facial features are rather undefined, atop her head is an intricate and beautifully sculpted hairstyle. The lower portion of the sculpture is a wide-brim skirt crafted out of wire mesh and adorned with 2000 colorful padlocks. This piece stood out to me, at least in part, because I have always loved the concept of representing eternal love and unbreakable bonds through the simple act of attaching a padlock to a bridge and throwing away the key. Not only did I appreciate Hazoumè’s creativity, but it made sense to me that a statue titled The Goddess of Love would borrow from this symbolic gesture. However, in reading the descriptive text which accompanies this work of art, it reveals that a focus in much of Hazoumè’s work is Fa: “a sacred initiation and divination system that lies at the heart of the voodoo religion.” It goes on to discuss how in voodoo, it is a serious act to close a lock and throw away the key (Hazoumè, wall text). I found this interesting because while in my interpretation, this piece is symbolic of the bridges on which padlocks are fastened and the keyed tossed into the water, the artist’s work pertains to a religion that condemns doing such a thing. Possibly, this sculpture is also a testament to the seriousness of closing a lock and tossing away the key, which is often a metaphor for making a promise.

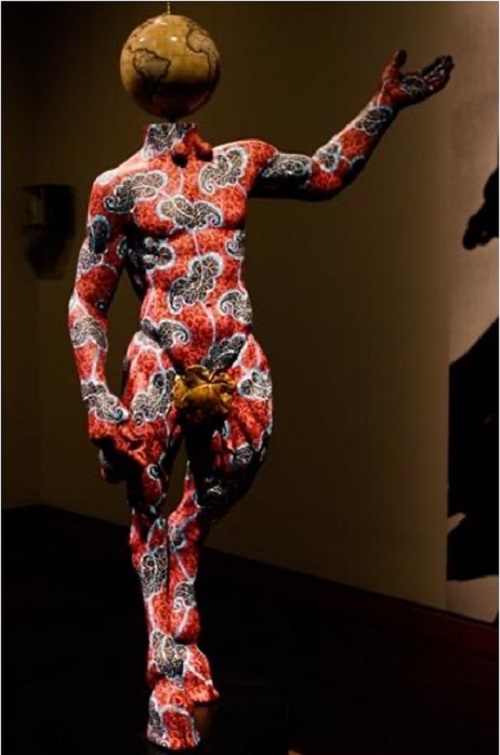

The second piece I want to discuss is Pan, created in 2018 (Arts of One World) by artist Yinka Shonibare, who was born in 1962 in London, UK (Shonibare). This eye-catching piece is a statue of a man, and could, in some way, be considered classical in that the figure is of a very idealized male body—what distinguishes this statue from more traditional marble statues, however, is his globe head, cloven feet, and hot pink body, covered in blue and burgundy paisley like patterns. He also has a golden leaf covering his genitals.  This piece captivated me for many reasons. Initially, it felt random, and I didn’t really understand the motivation behind it. I was drawn in by the smooth appearance of the “skin” on the figure, which is made of fiberglass (Arts of One World)—I was almost tempted to run my fingers along it. Also, as a fan of the fantasy genre, I have always been captivated by the concept of part human/part animal. What fascinated me most about this piece, however, was Shonibare’s choice to replace the head with a globe. Perhaps it is meant to challenge the colonial mentality of exploration and expansion, something that adversely affected millions of African people throughout centuries.

This piece captivated me for many reasons. Initially, it felt random, and I didn’t really understand the motivation behind it. I was drawn in by the smooth appearance of the “skin” on the figure, which is made of fiberglass (Arts of One World)—I was almost tempted to run my fingers along it. Also, as a fan of the fantasy genre, I have always been captivated by the concept of part human/part animal. What fascinated me most about this piece, however, was Shonibare’s choice to replace the head with a globe. Perhaps it is meant to challenge the colonial mentality of exploration and expansion, something that adversely affected millions of African people throughout centuries.

These two pieces intersect for multiple reasons. While (coincidentally) both artists were born in 1962, and the pieces were created within a relatively close time frame, these aren’t the similarities I’d like to discuss. In my view, the most relevant intersection between Hazoumè’s The Goddess of Love and Shonibare’s Pan is how each displays the human form. While it is evident that the styles of these two artists are very different, they both incorporate typically African elements—when you examine each of these statues, there is little question of the cultural inspiration behind these works. Both pieces rely on colour, texture, and patterns, and both relay a cultural message of some kind. While The Goddess of Love portrays the seriousness of closing a lock and throwing away the key, which, as noted, could be a testament or even criticism of the typically European lock bridges, Pan explores the notion of colonialism in Africa. Both figures are visually appealing and idealized in a sense, and accentuate the beauty of the human form. The pieces also sit at either end of the African section of the exhibit, which I found interesting— I was lucky enough to have had the opportunity to visit the exhibit twice, and the second time I felt as though The Goddess of Love greeted me as I entered, and Pan led me out as I exited.

Comments

No comments posted yet.

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!