Man of Mathematics

Illustrated by LIONEL MOSER

I met Willy Moser for the first time roughly one year ago. We talked about a math problem someone had sent him. Willy gave me 75 cents for my solution, but he also gave me something more: Our friendship was priceless. Willy was a tremendously inspiring person. I don't know anybody more enthusiastic about mathematics and about life than him. If you didn't have a chance to meet him, I hope that what follows will give you a sense of who he was.

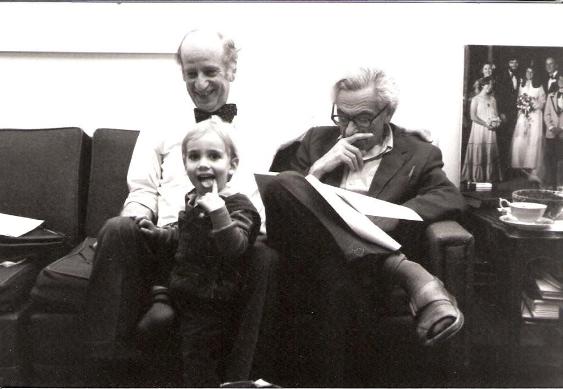

Professor Moser with grandson Adam and mathematician Paul Erdös in 1984. Photo courtesy of Lionel Moser. |

Editor's Note: In honour of Professor Moser, on Friday, March 13 Matthew de Courcy-Ireland will be presenting the lecture he was helping Professor Moser to prepare for McGill's Freaky Friday series:

Probability surprises -- Magic or Math?

For more information click here.

McGill Obituary, written by Robert Vermes and Will Brown

William O. J. Moser (1927--2009) was born in Winnipeg, and graduated in 1949 from the University of Manitoba, following which he obtained a Master's degree in Mathematics in 1951 at the University of Minnesota. Moser's Ph.D. Thesis, written at the University of Toronto under H. S. M. Coxeter, evolved into the oft-cited standard Ergebnisse reference on combinatorial group theory (1957) known to generations as ''Coxeter and Moser". Before arriving at McGill he held faculty positions at the University of Saskatchewan and the University of Manitoba. Much of his later seminal mathematical work was in the area now known as discrete geometry, where, with Peter Brass and Janos Pach, he published in 2005 Research Problems in Discrete Geometry. Moser's interest in problem solving extended far beyond this definitive monograph, and he was active for many years in provincial and national mathematics competitions for pre-university students, and in the publication for the Mathematical Association of America of Five Hundred Mathematical Challenges with E. Barbeau and M. Klamkin; with bawdy humour and other irreverence, problem solving was but one of the missions he shared with his older brother Leo Moser (1921--1970), who was also a mathematician.

Willy, as he was known to his friends, served as President (1973-1975) and in other capacities in the Canadian Mathematical Congress --- the predecessor to the Canadian Mathematical Society, and received their Distinguished Service Award in 2003. His experience in editing the Congress's journals served him well subsequently in multiple capacities, including editing his friends' writing --- whether or not they requested it. Moser's relations with colleagues were more brotherly than collegial. Typically one might find in his entourage a speed chess match, a peripatetic friend expounding latest discoveries and conjectures, and others enjoying the conversion to mathematics of the potent coffee Willy brewed for his academic family, all bathed in the pungent second-hand smoke of Willy's cigar or pipe. He stubbornly remained active as an Emeritus Professor at McGill after his retirement in 1997, and after a subsequent, debilitating stroke. On receiving the CMS Distinguished Service Award in 2003, he addressed the audience in these terms:

Be generous and patient as teachers, be active in projects which benefit the mathematical community and, above all, have as long and as happy a mathematical life as I have had, and am still having.

He will be missed.

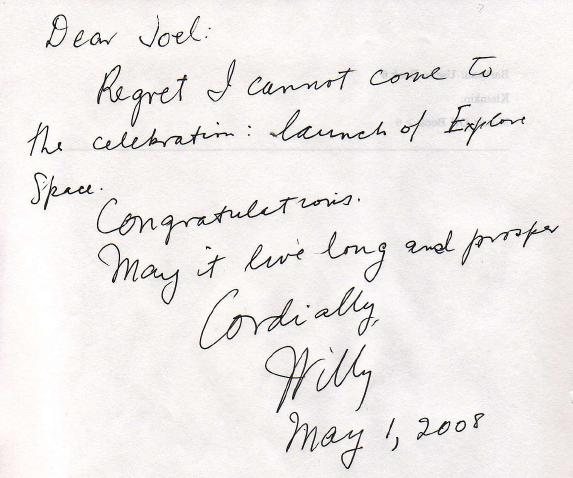

Professor Moser and SPACE

Professor Moser's connection to SPACE originated with his niece Barbara Moser, an English teacher at Dawson and SPACE member. Willy and and his wife Beryl, a longtime librarian at Dawson, welcomed us into their home for coffee and conversation and were always so generous with their time as we searched for our path to SPACE. He could not make it to the official launch of the project last May, 2008 but with the usual generosity and humour he was known for left us a note of encouragement:

Dear Professor Moser,

Thank you for your encouragement and guidance. Reflecting back on the conversations we had with the students about the idea of SPACE, it is very gratifying to see how far we have come. What begins with a simple idea becomes so much more when it is shared with others. Your stories and anecdotes of a life in mathematics captured our imaginations, inspiring us to pursue our hopes for SPACE and to explore without end. We will always be grateful for the stories you shared with us.

You will be missed,

--Joel and everyone in SPACE

Willy's Expo '67 Story

(Transcribed by Paula Moser from an oral version by Willy)

Expo 67, took place in 67, and a couple of weeks before the official opening there was a preview opening and the police station near the gambling joints recorded how many gifts were given out. They figured out the operators were giving back about $5 in prizes for every $100 they took in. So they looked for a mathematician to do an examination and decide if the games that were being played involved skill or not because the Canadian law was that if the game involved some skill then it was legal but if it was a game of pure chance, no skill, it was illegal. The chairman of the department recommended me and they hired me to do the job. The operators were operating ten different concessions. Simple ones. For example, the one I saw had circles drawn in a regular pattern on a board and people would throw dimes and if the dime fell inside one of the circles then they won a prize. There were sometimes smaller circles with bigger prizes, and so on.

So this happened just a few days before I was to leave for Minnesota where I worked that summer. I went down to the police station where they had removed this particular game from the concessionaire and they showed it to me so I said "okay, but I want to do an experiment. I will need 2000 dimes so I can duplicate what the play would be." They brought me a sack of 2000 dimes and I started throwing dimes onto the table. First of all from a distance of a few feet, the way a person playing the game would try and after 2000 tosses I figured out the probably of winning was .018 or .0018. It was two times in 1000 tosses. Then I started all over again, this time I moved right above the board and tried to drop the dimes so they would go into a circe. And it didn't change. I still won twice in 1000 tosses. So I gathered up the coins and this time I put a blindfold over my eyes and just tossed the coins down at random and I won again 2 times out of 1000 tosses. Thus proving that skill played no role in the game. It was a game of pure chance.

So the trial took place a week later and I was called as the expert witness by the police. The guys who operated the concessions, it was big business, they were mafia types. They operated hundreds of these things at fairs in the states and so they wanted to win this case. They hired Meyer Gross who was well known in Montreal and had never lost a case in court. The police asked me to testify and I did. Then the defense attorney started questioning me and whenever I tried to answer he cut me off. He was making fun of me, saying such things as "oh you call yourself a mathematician." He interrupted me so often that the judge said to him "keep quiet and let Professor Moser say what he wants." So I explained in great detail just what I've told you, how I played the game, and I deduced that you have my expert testimony that this was a game of chance. When the trial was over the judge immediately said that the prosecution wins the case, it was a game of chance. There was some question during the trial how much the prizes were worth. They used to give out a big doll and they claimed that the doll cost them $50 each.

When I walked out the wife of the guy who owned the concessions said to me "hey sonny, we pay $5 for those dolls." Anyway, I walked out into the bright sunshine, it was a hot day, and there about half a dozen detectives lined up, in short sleeved shirts, guns strapped at their sides, and everyone shook my hand because this was the first time that they had seen Mayer Gross lose a case.

The next day, I left for Minnesota and I came back for the end of August. At the beginning of September I called the detective, his name was Boisvert, and I said "Congratulations, you won the case." (By the way, it was written up in the newspaper, you can look for it, the Gazette article)

Beryl: No, I think it was in the Montreal Star.

Willy: Okay, the Montreal Star. Thank you. And ah...

Beryl: So you phoned Boisvert.

Willy: So, I phoned Boisvert and I said "Well now that we finished the court case, perhaps you should pay us something for the service." (In fact my student, Abramson, was helping me). So he said "okay, how much did you work." I said "well, we spent a few hours figuring it all out and there are two of us." He said "well, how much do you think is fair?" I said "well, I did this for the benefit of mankind, not to make money, but I think that if you gave us $400 for the two of us for the several days work it would be fine." He said "how about $300". So I said OK. A half an hour later, sirens blowing, they pull up to McGill in a car and Boisvert comes into my office and we shake hands and he says "$300 you get" and he opened up his wallet and he gave me cash which was really remarkable. However, I got even with him; I didn't report it as income.

That is the end of the story.

Comments

No comments posted yet.

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!