Hold Pet Owners, Not Pit Bulls, Responsible

Illustrated by Andrée-Anne Binette

Around September 2016, the city council of Montreal publicized its intention to ban pit-bull type dogs from the city (CBC News, “Montreal Passes Pit Bull Ban”). The mayor, Denis Coderre, has been one of the most active supporters of the proposed “By-Law Concerning Animal Control,” which demanded a dog-ownership permit from all current and potential dog owners. As well, it defined specific things that the government can and cannot do to one’s pet.

This dog legislation reveals a lot about the government’s perception of our relationship with non-human animals. In fact, I decided to criticize the misapplication of the dog policy by sending an argumentative e-mail to the mayor and to my borough representative, Luis Miranda, who are both important members of the city council.

To understand my political action process better, let’s delve into the overall history of the dog permit and regulation, the ways in which they are misapplied specifically in Montreal, and the institutions that I have dealt with to promote my stance on the issue. As well, I will discuss my political action and its efficiency – or lack thereof – in affecting the government.

To understand my political action process better, let’s delve into the overall history of the dog permit and regulation, the ways in which they are misapplied specifically in Montreal, and the institutions that I have dealt with to promote my stance on the issue. As well, I will discuss my political action and its efficiency – or lack thereof – in affecting the government.

Dog ownership permits and dog taxes have already been established in several locations, ranging from different countries to cities and provinces within Canada. Most American states, for example, require a dog license that is obtainable and valid only as long as that the canine’s vaccines are up to date (Pajer). In Ireland, dog licenses are also mandatory and cost the same for any dog breed, varying only according to the permit’s duration of validity (“Dog Licensing in Ireland”). In other places, like in Montreal, dog permits are more restrictive or costly depending on the type of dog that one fosters: therefore, pit-bulls face harsher regulations than Pomeranians, sometimes implying euthanasia as punishment for aggression, as mentioned earlier.

In all the aforementioned locations, it does not seem that the dog owner’s caretaking ability is taken into consideration. It seems that most countries only want to make sure that the dog is identified, rather than to guarantee that it is treated and educated well. The best system that I have found is the one in New Zealand. There, the “Dog Control Act 1996” made it mandatory for all adult dogs to be microchipped and registered in its city council’s database. Registration fees, per article 37 of the Act, differ according to factors including whether the dog is neutered or spayed, whether it resides in an urban or a rural area, and, most importantly, whether its owner exhibits responsibility in its dealings with the pet. Indeed, this is my first encounter with a system that includes the owner’s accountability to the dog as a variable in the equation. This type of logic is what I wish guided Montreal’s pet policy, but with the current by-law, it seems that we are far from logic.

Under the current by-law, Montreal authorities can order “to have euthanized any animal that is dangerous, at-risk, prohibited, stray, dying, gravely injured or highly contagious,” where dangerous animals include pit-bulls, regardless of their nature, and at-risk animals include dogs that have ever attempted to bite another animal, human or other (“By-Law Concerning Animal Control” 3). Furthermore, in the new policy, the responsibility of the crime is entirely placed on the animal, instead of focusing on its owner. I believe that the legislation should instead address the owner, a being capable of reading and understanding written legislature. It is the dog owner who agrees, according to the liberal theory of social contract, to subject himself or herself to the rule of law for the benefits of civilization. The dog, the cat, and the hamster are incapable of the abstract thinking that permits them to see the benefits of society. The new by-law should instead target the owner. It is the pet owner who should train and educate the pet, not completely unlike the way we expect a parent to be responsible for educating a child. When a child plays with a gun and shoots his or her friend, the child is not sent to jail. The parents are punished for leaving the gun in plain view and not educating or observing their kid. By analogy, the pet, like the child, should not be legally liable for their actions: their educator should take responsibility for his or her negligence. In sum, the entire legislation should shift its focus from punishment of the dog to enforced education of the person who raises it.

Another problematic part of the new policy is the wrong application of the permit. Dog permits can be bought, not necessarily earned. There is no financial evaluation of whether or not the owner can afford a pet, no tests checking if he or she is responsible enough, and whether or not the individual can train the animal, keep it healthy, safe and friendly. There are no caretaking courses, no mandatory dog training programmes. I advocate for a better-informed permit distribution for new dog owners, through a screening process that evaluates whether an individual is financially and emotionally fit for such a responsibility. I also support the launch of mandatory dog training courses and information sessions, as it is done in the process of driving license acquisition. Also, similarly to driving licenses, the city should issue different permit levels for different dog species: the large, and powerful Caucasian shepherd should not require the same credentials as a Pekingese. If these principles are applied, the dog permit would shift from a purchasable token allowing a citizen to own a dog into a symbol of privilege earned through work and acquisition of knowledge.

My stance on the issue, suggesting that humans are not naturally reasonable enough to care for a dog, is definitely not liberal, especially in the classical sense of the term. Early liberals assume that the human being is innately rational, and can achieve quasi-perfection through study. My writings, however, suggest that the unprepared human tends to be irrational, and information can lead him or her to augmented reason, but never to perfect understanding. Moreover, I perceive social ecology in my ideology, in the sense that I see mankind as one with nature but, given our extended social and technological advancement, we must act as responsible vanguards in order to protect nature. Our relationship with dogs should be founded upon caring and responsibility. This relates to the view of humans as “active and creative stewards of the natural world” in the social ecology perspective (Mintz et al. 92). All the roots of my ideology point to one belief: we must not allow an “unenlightened” living being to suffer because our flawed system allowed an uninformed human to experiment with its life.

In order to improve the system that would allow such injustices, a citizen must contact the forces that regulate and affect any given issue. In the case of “By-Law 16-060,” we are dealing with the court and the city of Montreal administration. The city council includes 65 people – the mayor, borough representatives, and various counselors – who treat issues including social security, environmental well-being, and intergovernmental relations. It meets almost every month in order to discuss current issues and communicate with concerned citizens (“Conseil Municipal - Mission”). The current mayor, Denis Coderre, being the one who proposed and defended the bill most loyally, seems to be the best person to address when asking for a change. In his own words, his motives for banning pit-bulls and passing the new by-law were the following: "My duty as mayor of Montreal is making sure I am working for all Montrealers, […] And I am there to make sure they feel safe and that they are safe" (CBC News, “Montreal Passes Pit Bull Ban”). I understand and agree that, as a mayor, he must put the safety of humans first. However, safety must not be confused with oppression of beings who are weak and defenseless in our legal system. Although Coderre is right in his will to protect the populace, I strongly believe that he is doing it in the wrong ways.

Consequently, I wrote a persuasive e-mail in his address to try to convince him first of all that there are other alternatives for effective animal control. Wanting to maximize the efficiency of my demands, I also sent a copy of the e-mail to my borough representative, Luis Miranda. Miranda was initially against the by-law (CBC News, “How Did Your Councillor (sic) Vote on the Pit Bull Bylaw?”). I hope that, having contacted him, his opposition will be reinvigorated.

I chose this particular form of action – that is, writing a letter – because, according to a study by the Congressional Management Foundation, personalized e-mails have a high, 88%-chance of influencing policy to at least some extent (3). Although postal letters have a 2%-higher success rate, an e-mail would be delivered faster, which was a priority considering the limited time given for the project. I also strategically decided to write in French. Although receiving letters in different languages might give the governance the impression that the by-law affects many different sub-groups of the population, I work for the government and I know from experience that many government agents are almost exclusively francophone. I wanted my content to be clearly understood and interpreted in a non-biased way. Writing an e-mail was therefore best way to affect the by-law according to what I found in the research and because of the knowledge of my own capacities.

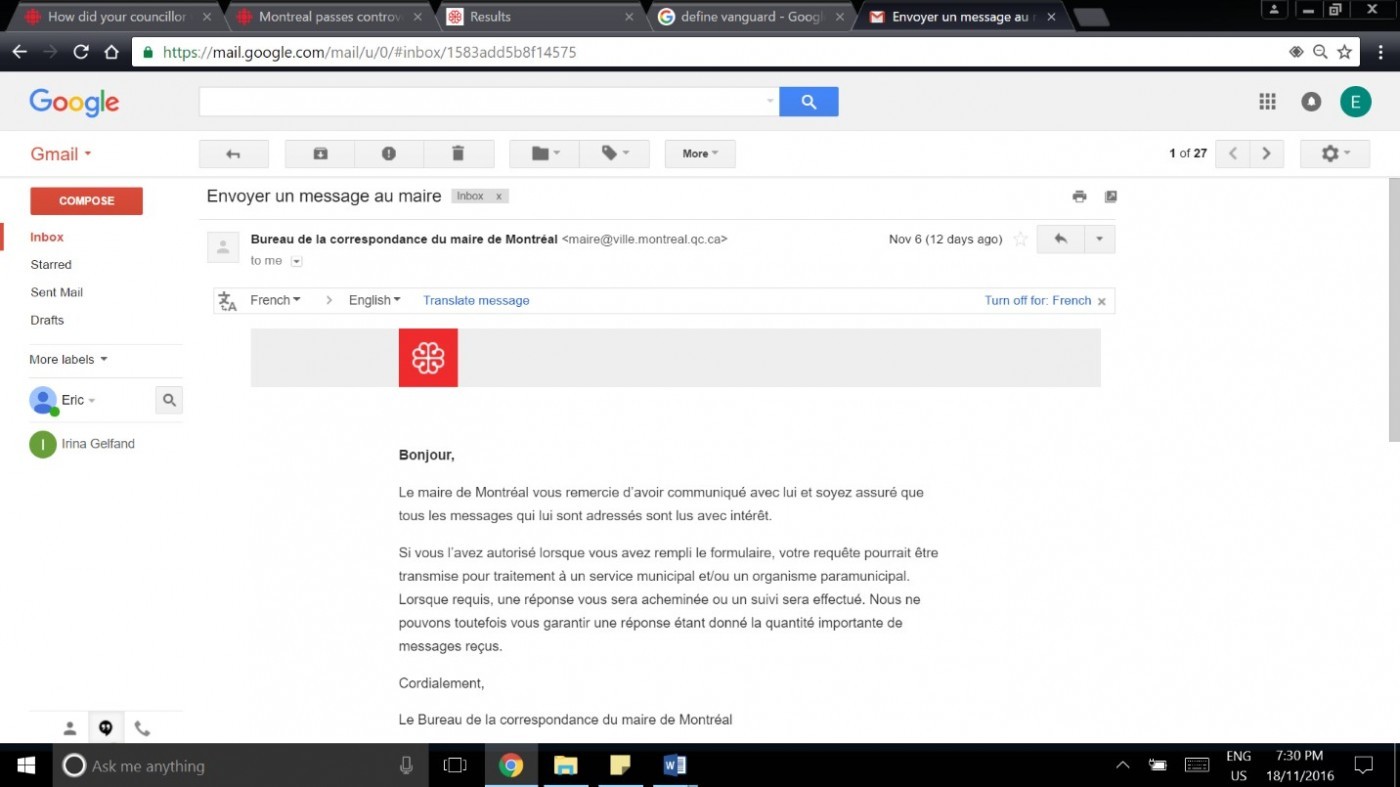

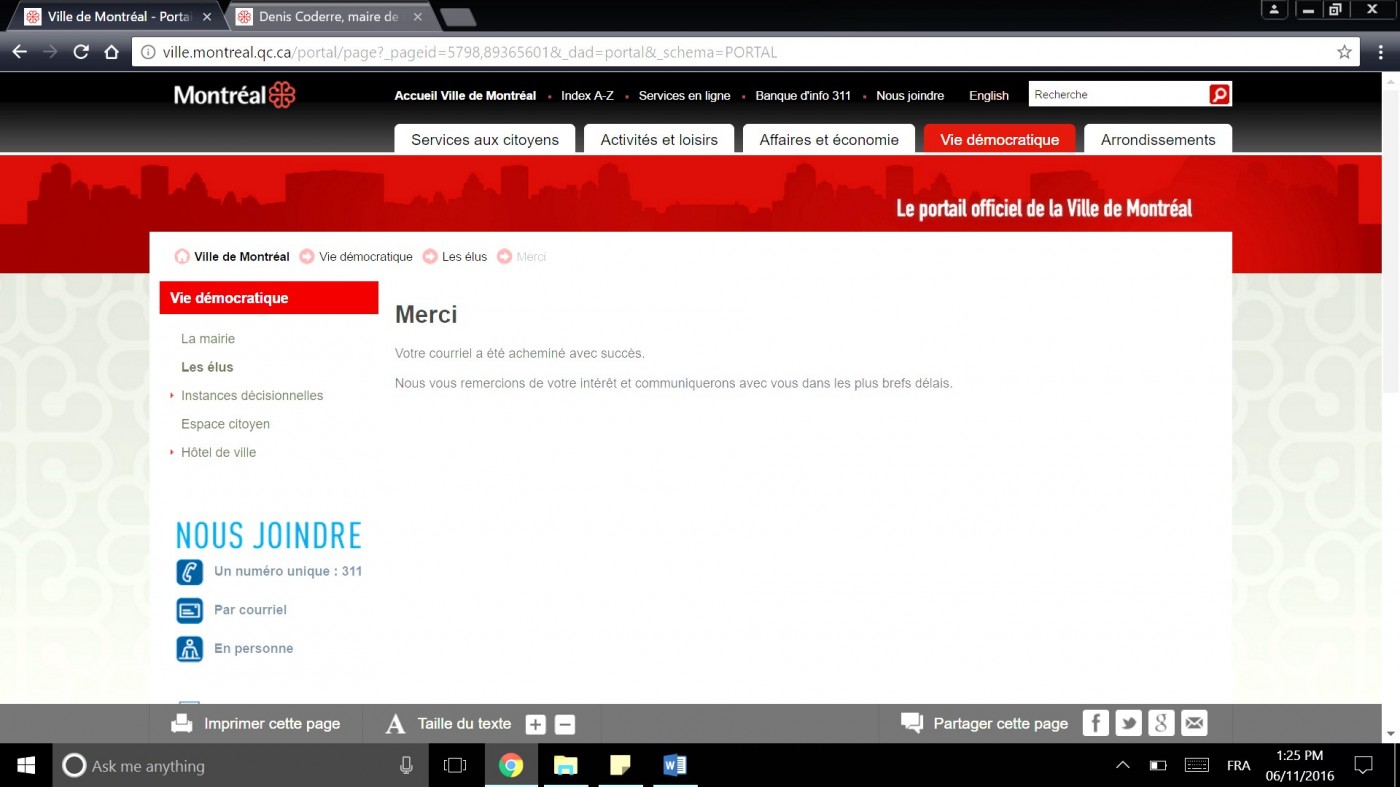

I composed a letter that could perhaps be considered as a summary of this very essay (see appendix A). Both e-mails were sent November 6th, 2016, but unfortunately no answer has been received.

Multiple factors may have caused the lack of response. As mentioned in the automated confirmation of receival that was sent to my e-mail address (see appendix B), the municipal council and especially the mayor must receive dozens of messages each day, and processing them all must take a lot of time. Another reason for not replying could be that the By-Law has already passed, and is now in place. The city might not want to reopen the case at this point to revert changes and lose money and time. Either way, unless the mayor wants to personally write a physical letter and send it to my residence, I do not see a reason for there not to be at least some message rejecting my demands.

The lack of response makes me feel two different things simultaneously: first, I feel like my voice is not getting heard, and that our system lacks political efficacy. I feel that I cannot affect its decisions, especially ones that are already in place and might need revision. Secondly, even if Coderre and Miranda eventually answer my calls, I believe a municipal government must answer citizens’ complaints in no more than two weeks. This is even truer for Miranda: he is a borough representative, which means that less people can contact him directly. This should imply shorter response times. Whatever the problem is, I only hope that the issue of the animal control by-law will be brought back up during the Council’s next meeting.

In conclusion, the political action project mostly made me regret not having engaged with this issue earlier. Our relationship with non-human animals is becoming an increasingly hot topic worldwide, and pet regulation, as I showed, often reveals inconsistencies between the views of citizens such as myself and those of governments. To fix such inconsistencies, one must act, but the method and time of action are crucial to its success. My e-mail did not receive a response from neither the mayor or my representative, which made me doubt whether or not the government actually listens to the governed at times other than elections. The lack of response may be due to my late timing, or maybe to my method of contact or even the style of writing. However, such factors should not affect the municipality’s responsiveness so strongly that it fails to answer altogether. I will keep waiting for an answer, but maybe not keep pushing it if the issue is already settled. The government has interesting ways of controlling the political agenda, and not answering letters might be one of them. However, if the by-law controversies resurface, I will for sure actively support protesters.

Appendix A: The E-Mail

Sujet : Le nouveau règlement sur le contrôle des animaux

Cher monsieur Coderre,

Je m’appelle Eric Alex Kleonin, élève à temps plein au collège Dawson. J’ai récemment eu vent de l’instauration d’un nouveau règlement de chiens, incluant une demande de permis, à la ville de Montréal, et j’aimerais en discuter avec vous. Non, ce n’est pas encore une lettre concernant les chiens de type Pit-bull ; plutôt, je souhaite discuter de la nature du règlement lui-même. Je dois vous avouer que je trouve que l’idée est bonne – elle prouve que la possession d’un animal de compagnie est un privilège et non un droit – mais son application est fautive.

D’abord, sous le nouveau règlement, les autorités montréalaises peuvent « ordonner l’euthanasie d’un animal dangereux, à risque, interdit, errant […] ou hautement contagieux » (Règlement sur le contrôle des animaux, page 3). Dans cet énoncé, un animal dangereux inclut tous les chiens de type pit-bull, sans exception, et un animal à risque se réfère à tout animal qui a déjà essayé de mordre un autre être vivant. Ainsi, le chien peut être condamné à mort s’il transgresse les standards de moralité humains, des standards qu’il n’a pas les moyens d’apprendre. C’est paradoxal ! Dans la société libérale où l’on vit, la légitimité de la loi est basée sur le fait que ses sujets peuvent y accéder et la comprendre. Ainsi, tout individu accepte d’échanger sa liberté pour les bienfaits de la civilisation. Par contre, un animal non-humain est incapable de saisir une pensée abstraite de même. L’application de concepts comme la peine de mort – que même nous, humains, rejetons – à des animaux est au moins grotesque. On peut abattre un animal hors de contrôle, s’il compromet la vie des autres, mais ceci s’applique seulement à un animal qui ne peut être contrôlé par personne. Si c’est le maitre qui est incapable de maitriser la bête, l’animal ne doit pas en subir les conséquences.

En effet, la philosophie derrière le règlement met toute la responsabilité du méfait sur l’animal à la place de l’homme. La législation, ne doit-elle pas s’adresser à celui qui est capable de la lire ? Enfin, si par l’institution d’un permis de chien, on traite la possession d’un animal comme une responsabilité (similairement au fait de conduire), celui qui en profite doit aussi être celui qui en subit les conséquences. Souvent on dit qu’avoir un chien, c’est comme avoir un enfant. Lorsqu’un enfant américain joue avec une arme à feu et tire sur son ami, il n’est pas envoyé en prison. Les parents sont ceux qui subissent une peine légale pour avoir laissé l’arme en pleine vue et pour avoir failli à leur tâche de gardiens. Le chien, comme l’enfant, ne doit donc pas être légalement assujetti aux conséquences de ses actions.

De plus, au-delà de la philosophie du règlement, il reste des problèmes au niveau du permis lui-même. Ce dernier peut être acheté sans être mérité. Il ne prouve pas que la personne est effectivement un bon maitre de chien. Il n’y a point d’évaluation financière vérifiant si la personne peut se tolérer un animal, d’examens qui testent si l’individu est assez responsable, s’il est capable de bien élever l’animal, le garder sain, sauf et pacifique. L’adoption d’un animal de compagnie est toujours accessible à n’importe qui, tant que la personne est capable de payer les couts fixes du permis et le prix de l’acquisition du chien. Si, par la suite, le chien se comporte mal par faute de manque d’encadrement, l’euthanasie l’attend. C’est complètement absurde ! En contraste, un permis de conduire ne peut pas être acheté. Pour pouvoir s’assoir derrière le volant, une personne doit obligatoirement assister à des cours théoriques et pratiques et passer les évaluations pertinentes. Pourquoi ne ferait-on pas quelque chose de semblable pour le permis de chien ? Moi, je suggèrerais de débuter des cours de dressage obligatoires, des programmes de gardiennage de chiens, ainsi qu’un procès d’évaluation financière et psychologique plus rigoureux. Si on considère un chien comme ayant un potentiel de destruction similaire à une voiture, alors on doit s’assurer que les personnes qui veulent en acquérir un sont capables de le maitriser. Des permis différents pour des différents chiens sont aussi recommandés : on ne peut pas être s’attendre que quelqu’un habitué au pékinois puisse manier un berger du Caucase.

Je comprends que le processus engendrerait des couts administratifs plus élevés, et peut-être même ralentira les taux d’adoption de chiens errants. Par contre, si on a le « devoir de protéger la population » en tête, il faut s’assurer que ce n’est pas n’importe qui qui peut adopter n’importe quoi.

Je vous remercie de votre attention et j’attends sincèrement votre réponse,

Eric Alex Kleonin

eric.alex.kleonin@gmail.com

Appendix B: Proof of Transmission of the Message to Denis Coderre

Appendix C: Proof of Transmission of the Message to Luis Miranda

Bibliography

“By-Law Concerning Animal Control.” Ville De Montréal, 26 Sept. 2016, [url=http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/sel/sypre-consultation/afficherpdf?idDoc=27629&typeDoc=1]http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/sel/sypre-consultation/afficherpdf?idDoc=27629&typeDoc=1[/url]. Accessed 23 Oct. 2016.

CBC News. “How Did Your Councillor Vote on Montreal's Controversial Pit Bull Bylaw?” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 28 Sept. 2016, [url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/pitbull-bylaw-vote-breakdown-1.3781452]http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/pitbull-bylaw-vote-breakdown-1.3781452[/url]. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2016.

CBC News. “Montreal Passes Controversial Pit Bull Ban.” CBCnews, CBC/Radio Canada, 27 Sept. 2016, [url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/montreal-pit-bull-dangerous-dogs-animal-control-bylaw-1.3780335]http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/montreal-pit-bull-dangerous-dogs-animal-control-bylaw-1.3780335[/url]. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2016.

“Conseil Municipal - Mission.” Ville De Montréal. [url=http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=5798,85933596&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL]http://ville.montreal.qc.ca/portal/page?_pageid=5798,85933596&_dad=portal&_schema=PORTAL[/url]. Accessed on 23 Oct. 2016.

“Dog Licensing in Ireland. Dog Licenses from An Post.” An Post, An Post, [url=http://www.anpost.ie/AnPost/GeneralTemplates/ProductsAndServices.aspx?NRMODE=Published&NRNODEGUID=%7B0CEF4EAB-DE73-4250-9876-69F955B3A83C%7D&NRORIGINALURL=%2FAnPost%2FMainContent%2FPersonal%2BCustomers%2FMore%2Bfrom%2BAn%2BPost%2FDog%2BLicence%2F&NRCACHEHINT=Guest#Howmuch#Dog]http://www.anpost.ie/AnPost/GeneralTemplates/ProductsAndServices.aspx?NRMODE=Published&NRNODEGUID=%7B0CEF4EAB-DE73-4250-9876-69F955B3A83C%7D&NRORIGINALURL=%2FAnPost%2FMainContent%2FPersonal%2BCustomers%2FMore%2Bfrom%2BAn%2BPost%2FDog%2BLicence%2F&NRCACHEHINT=Guest#Howmuch#Dog[/url]. Accessed on 18 Nov 2016.

Mintz, Eric et al. Politics, Power and the Common Good: An Introduction to Political Science. 4th ed., Toronto, Pearson Prentice Hall, 2014.

New Zealand, Department of Internal Affairs. “Dog Control Act 1996.” New Zealand Legislation, 2 May 1996, [url=http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1996/0013/latest/DLM374410.html]http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1996/0013/latest/DLM374410.html[/url]. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2016.

Pajer, Nicole. “5 Reasons to Get Your Dog Licensed.” Cesar's Way, Cesar's Way Inc., 10 Dec. 2015, [url=http://www.cesarsway.com/get-involved/bringing-new-dog-home/5-reasons-to-get-your-dog-licensed]http://www.cesarsway.com/get-involved/bringing-new-dog-home/5-reasons-to-get-your-dog-licensed[/url]. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2016.

“Perceptions of Citizen Advocacy on Capitol Hill.” Congressional Management Foundation, Adfero Group, Blue Cross Blue Shield Association and CQ Roll Call, 2011, [url=http://www.congressfoundation.org/storage/documents/CMF_Pubs/cwc-perceptions-of-citizen-advocacy.pdf]http://www.congressfoundation.org/storage/documents/CMF_Pubs/cwc-perceptions-of-citizen-advocacy.pdf[/url]. Accessed on 24 Oct. 2016.

Comments

Raja A Rehman

March 14, 2018Thanks for Worth Sharing - very much informative

<a > prevent fleas and ticks</a>

Raja A Rehman

March 14, 2018http://www.petoclub.com/how-to-prevent-fleas-and-ticks/

Raja A Rehman

March 17, 2018You Publish a very nice article - i love it

Internal bleeding in dogs, all u need to know

https://www.petoclub.com/internal-bleeding-dogs/

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!