A Pioneer for Public Health

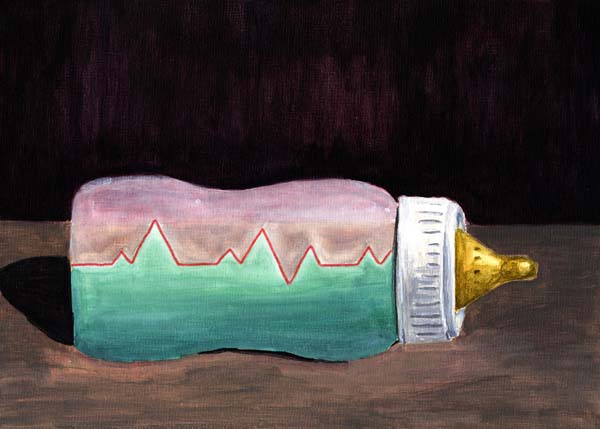

Illustrated by Francis Esperanza

Sara Josephine Baker (1873-1945) was an American physician who worked for the Department of Health in New York City. She is known for having twice tracked down Mary Mallon, famously known as Typhoid Mary, an Irish cook who was the first person in the U.S. identified as an asymptomatic carrier of the pathogen associated with Typhoid fever, meaning she was infected but displayed no symptoms, and she was presumed to have infected 51 people, 3 of whom died.

But Baker was best known for her contributions to public health, particularly for children and infants in poor urban immigrant communities. She was the first director of a children’s public health agency and gained much publicity when she told a New York Times reporter it was, “six times safer to be soldier in the trenches of France than to be a baby born in the United States.” Although her work in public health was not very technical, it was invaluable, and a display of how basic education on health and hygiene could drastically improve people’s health and save lives.

But Baker was best known for her contributions to public health, particularly for children and infants in poor urban immigrant communities. She was the first director of a children’s public health agency and gained much publicity when she told a New York Times reporter it was, “six times safer to be soldier in the trenches of France than to be a baby born in the United States.” Although her work in public health was not very technical, it was invaluable, and a display of how basic education on health and hygiene could drastically improve people’s health and save lives.

Health departments such as Baker’s were a response to the epidemics of infectious diseases such as smallpox, cholera, and yellow fever, which prompted the creation of these organizations in the 19th century. These departments started massive sanitation projects to bring clean water to cities, as well as to institute efficient sewage disposal, garbage collection and disposal, vaccination programs, isolation hospitals, and clinics (Leavitt 609-610). Most 19th century work had rested on the medical theory that dirt caused disease, so it emphasized keeping cities clean. People believed that vapours called miasma (which is ancient greek for “pollution”) rose from the soil and spread diseases, often believed to come from rotting vegetation and foul water, especially in swamps and urban ‘ghettos’. Night air was considered dangerous in many western cultures, leading people to avoid breathing it in and keeping windows and doors shut.

The medical community was divided on the explanation for the proliferation of disease. There were “contagionists” who thought disease spread through physical contact, and others who believed that disease was already present in the air in the form of miasma. Physician John Snow’s study of the 1854 Broad Street Cholera Outbreak in Westminster London studied the causes and hypothesised that germ-contaminated water was the source rather than miasma. This discovery influenced public health and the improvement of sanitation facilities starting in the mid 19th century.

In second half of the 19th century, French microbiologist Louis Pasteur and German microbiologist Robert Koch revolutionized medical theory about the causes of epidemic diseases. The etiology (study of the cause) of diseases was no longer of the entire environment; it was narrowed down to the examination of microscopic germs. Bacteriology affected public health theory, practices, and consequently the work of Sarah Josephine Baker.

At the beginning of Baker’s career in the early 20th century, the infant mortality rate was so high, 1500 babies routinely died of dysentery every week during the summer. At the turn of the century, “Hell’s Kitchen” was considered the worst slum in New York City, with up to 4,500 people dying every week. Preventive medicine barely existed at the time and hygiene standards were vastly different. (Typhoid Mary likely contaminated people because she did not wash her hands with soap before touching or preparing food.) Additionally, the Health Department was allegedly corrupt and ineffective. In Baker’s own words, “It reeked of negligence and stale tobacco smoke and slacking.” (Baker 56).

In contrast to many of her colleagues who emphasised laboratory-based public health, Baker focused on preventive health measures and the social context of disease. Baker tested her theories about preventative medicine in 1908, with an experiment in a lower-class neighbourhood; all new mothers in the district were visited at least once by a nurse who instructed them in basic healthy-newborn care, which encouraged bathing, how to keep them from getting hot, how to keep them from suffocating in their sleep, suitable ventilation and clothing, and breast-feeding of infants to avoid commercial unpasteurized milk. As a result there was a decrease of more than a thousand neonatal deaths while infant mortality elsewhere had not changed (M.N.S.).

Baker also licensed midwives (and consequently weeded out incompetent caregivers); previously most midwives had received no formal training, and often relied on folk medicine. Baker established “baby health stations” which distributed milk, and established “Little Mothers’ Leagues”, which taught older siblings basic principles of nutrition and hygiene to better care for their siblings at a time when they were often the primary caretakers while their parents worked. She systematically implemented health education reforms into schools, worked to make sure each school had its own doctor and nurse, and ensured that children were routinely checked for infections. This system worked so well that once rampant diseases like head lice and the eye infection trachoma became almost non-existent.

Besides improving the community’s education regarding health, Baker was also innovative in several regards. She risked her professional reputation by modifying milk content according to the weight of individual babies, a tactic that proved nutritionally effective, although against the prevailing pediatric opinion of the time. Baker invented an infant formula made out of water, calcium carbonate, lactose, and cow milk, which enabled mothers to go to work so they could support their families. She helped design such items as receptacles for drugs to fight blindness at birth and patterns for hygienic baby garments (subsequently used by the McCall Pattern Company).

Baker aided in the prevention of infant blindness, a scourge caused by gonorrhoea bacteria transmitted during birth. To prevent blindness, babies were given drops of silver nitrate in their eyes. Before Baker, the bottles in which the silver nitrate was kept would often become unsanitary, or would contain doses that were so highly concentrated that they would do more harm than good. Baker designed and used small containers made out of antibiotic beeswax that each held a single dose of silver nitrate, so the medication would stay at a known level of concentration and could not be contaminated. Blindness subsequently decreased from 300 babies per year to 3 per year within 2 years.

Although not widely known, Baker and the techniques she used had an important impact in the public’s health education, health services offered to the disenfranchised, the development of health departments, and community outreach in medicine. Perhaps part of the reason she is lesser known can be attributed to her gender, and the fact that her work centered largely on helping children from poor immigrant families, so it was seen as less legitimate or important. In her own 1939 autobiography, Fighting For Life, Baker herself at times shows disdain towards the people she helped. Nevertheless by the time Baker left city government in 1923, 48 states had a Bureau of Child Health, 35 states had implemented versions of her school health program, and New York City had the lowest infant mortality rate of any major American city (Parry). She detailed her work in her autobiography, considered to be witty, engaging, and thought-provoking even today. Baker was not the only one who helped to advance and modernize public health at the time, but she is remarkable in her approach to medicine. In addition to seeing Baker as a revolutionary, we can also better understand through her experience where public health was at that time, where it had been before then, and how it has progressed since.

Comments

No comments posted yet.

You have to be registered and logged in in order to post comments!